Why sustainable development matters: commons conservation

By Dr. Darian McBain

Imagine a small community discovers a plot of land and it’s decided that as there is no owner, it will be perfect for everyone to use to raise one animal per person to meet their needs.

This situation is satisfactory for some time, but eventually, some start to raise more than one animal. After all, the land isn’t managed so there is no way to enforce the rules. Eventually, without regulation, everyone is overusing the common resource in order to serve their own interests, and the land is unable to sustain the number of animals using it. Soon, it becomes degraded and is unable to support any type of activity.

This thought experiment was first proposed by the economist William Forest Lloyd, to demonstrate the effects of unregulated grazing on the common land in the British Isles. It was then utilized by Garrett Hardin one hundred years later, as he looked at the inevitable problems faced by any shared and unregulated resource.

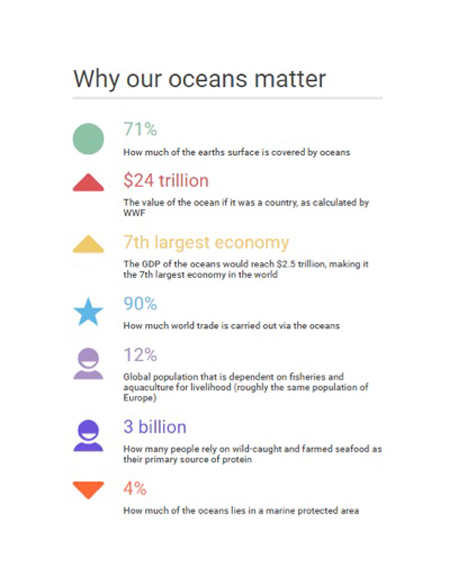

No example is perhaps as relevant in today’s society our world’s oceans. It is our largest natural resource; in terms of land mass, it is 8 times bigger than the continent of Asia. It produces nearly half of the oxygen we breathe and holds an estimated 80% of the earth’s mineral resources. Yet, only 4% lies within a marine protected area.

The oceans are no man’s land, literally. Especially since the United Nations has stated that no country can claim ownership over any part of the high seas which has meant that we are all at equal liberty to utilize them.

Now our oceans are facing big problems such as illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing, a global issue that adversely impacts ocean fisheries and marine eco-systems. Due to the black market nature of this activity, it is difficult to get precise figures on how much fish is caught this way, but estimates range from 11-26 million tonnes.

Then there are big climate change issues. The oceans are warming and becoming less oxygenated and more acidified. This will change ocean chemistry and impact life underwater.

Meanwhile, it becomes difficult for common goals to be achieved as commercial interests are often pitted against marine conservation efforts in a way that breeds mistrust.

In short, 183 years later and the hypothetical, overused common land is looking a lot realer, bluer and wetter than we would like.

However, there is little inevitable about this. A global oceans management strategy would support international and multi-stakeholder solutions, and many of these ideas are already underway.

In 2016, the United Nations released their Sustainable Development Goals for 2030 and included the conservation and sustainable use of oceans, seas and marine resources. This means that ocean conservation is a target member states should be framing their agendas around for the next 15 years.

In March, negotiations began on the establishment of an international agreement, which would provide a cohesive management structure to the governance and use of the seas. This is an important step towards solving these problems as it will identify actors responsible for driving change.

The establishment of diverse multi-stakeholder platforms such as the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation and the National Fisheries Institute are examples of how different groups with different philosophies can come together to cooperate on key issues.

We should remember the scope of the problem we are facing. However, there is much to discuss with regards to a commons conservation effort. This is taking place right now at an international, grassroots, industry and regional level. Perhaps it’s a little late, but there is nothing inevitable about this commons tragedy just yet.